Charles Pinck

70th Anniversary of OSS Founding

June 2012

Glorious Amateurs Needed

January 2010

Published in Sphere

As Congress prepares to start hearings on the Christmas Day attack on Northwest Airlines Flight 253, there will be an inevitable focus on how to use the latest technology – better databases, full-body scanners and the like – to detect and prevent future attacks.

But the fact is that despite remarkable advances in technology, intelligence remains a distinctly human endeavor. There is no machine that can substitute for a human being's intellect, judgment, instinct or courage.

And if lawmakers want to truly reform our intelligence community, they would be wise to look backward instead of forward – all the way back to World War II's Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor to the CIA and U.S. Special Operations Forces.

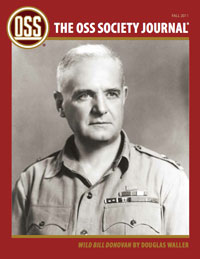

This "unusual experiment," as its visionary founder, Maj. Gen. William J. "Wild Bill" Donovan, described it in his 1945 farewell address, succeeded principally because of its diverse and brilliant personnel, many of whom probably would never get admitted into today's intelligence services.

Read More...

As Congress prepares to start hearings on the Christmas Day attack on Northwest Airlines Flight 253, there will be an inevitable focus on how to use the latest technology – better databases, full-body scanners and the like – to detect and prevent future attacks.

But the fact is that despite remarkable advances in technology, intelligence remains a distinctly human endeavor. There is no machine that can substitute for a human being's intellect, judgment, instinct or courage.

And if lawmakers want to truly reform our intelligence community, they would be wise to look backward instead of forward – all the way back to World War II's Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor to the CIA and U.S. Special Operations Forces.

This "unusual experiment," as its visionary founder, Maj. Gen. William J. "Wild Bill" Donovan, described it in his 1945 farewell address, succeeded principally because of its diverse and brilliant personnel, many of whom probably would never get admitted into today's intelligence services.

Read More...

'Basterd'ized History

September 2009

Published in The Washington Times

By Charles T. Pinck

An 'inglourious' view of the intelligence services

Given the very close relationship between Hollywood and World War II's Office of Strategic Services (OSS), forerunner of the CIA and U.S. Special Operations Forces, whose ranks included director John Ford and actors Robert Montgomery and Sterling Hayden, it's troubling that Hollywood has distorted the history of the OSS in two recent major motion pictures, "The Good Shepherd" and "Inglourious Basterds."

These two movies present diametrically opposite but equally false assertions about the OSS, particularly about the important role played within the organization by Jews and other minorities.

In "The Good Shepherd," OSS founder Maj. Gen. William J. Donovan (portrayed as Gen. William Sullivan in the movie), recruits Matt Damon's character, a member of Yale's Skull and Bones, to join OSS by telling him, "We are looking for honorable and patriotic young men. No Jews, no blacks, and only a few Catholics."

The notion that Gen. Donovan -- a devout Catholic -- would say such a thing is preposterous. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Read More...

By Charles T. Pinck

An 'inglourious' view of the intelligence services

Given the very close relationship between Hollywood and World War II's Office of Strategic Services (OSS), forerunner of the CIA and U.S. Special Operations Forces, whose ranks included director John Ford and actors Robert Montgomery and Sterling Hayden, it's troubling that Hollywood has distorted the history of the OSS in two recent major motion pictures, "The Good Shepherd" and "Inglourious Basterds."

These two movies present diametrically opposite but equally false assertions about the OSS, particularly about the important role played within the organization by Jews and other minorities.

In "The Good Shepherd," OSS founder Maj. Gen. William J. Donovan (portrayed as Gen. William Sullivan in the movie), recruits Matt Damon's character, a member of Yale's Skull and Bones, to join OSS by telling him, "We are looking for honorable and patriotic young men. No Jews, no blacks, and only a few Catholics."

The notion that Gen. Donovan -- a devout Catholic -- would say such a thing is preposterous. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Read More...

OSS Invasion of Martha's Vineyard

August 2008

By Charles Pinck

The Martha's Vineyard Times

August 28, 2008

Earlier this month the National Archives released personnel files from World War II's Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency and U.S. Special Forces, which was founded and led by the legendary Major General William "Wild Bill" Donovan, the only American to receive our nation's four highest military honors. OSS luminaries included famed chef Julia Child, Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Nobel Prize winner Ralph Bunche, movie director John Ford, Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, actor Sterling Hayden, writer John O'Hara, the artist Saul Steinberg, baseball player Moe Berg, among many others. General Donovan called them his "glorious amateurs."

OSS was a perfect reflection of General Donovan's character: a potent combination of brains, brawn, and bravado. General Donovan encouraged OSS personnel to take risks, frequently telling OSS personnel that, "you can't succeed without taking chances." Leading by example, General Donovan took the same risks himself. Members of OSS volunteered for the most dangerous missions of World War II behind enemy lines to conduct sabotage and guerilla warfare and work with local resistance groups. Their capture by the enemy meant certain death.

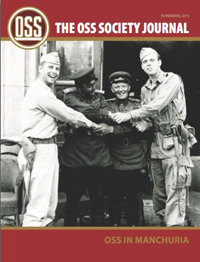

Intelligence provided by OSS was critical to the success of Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa. Allen Dulles, chief of OSS operations in Switzerland, secretly negotiated the early surrender of German troops in Northern Italy. Fritz Kolbe, a German diplomat and an OSS asset, provided the U.S. with some of the most valuable intelligence of the war. Some of the most significant contributions came from leading academics in its Research and Analysis division. The Science and Technology branch devised imaginative new weapons and other espionage tools.

Read More...

The Martha's Vineyard Times

August 28, 2008

Earlier this month the National Archives released personnel files from World War II's Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency and U.S. Special Forces, which was founded and led by the legendary Major General William "Wild Bill" Donovan, the only American to receive our nation's four highest military honors. OSS luminaries included famed chef Julia Child, Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Nobel Prize winner Ralph Bunche, movie director John Ford, Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, actor Sterling Hayden, writer John O'Hara, the artist Saul Steinberg, baseball player Moe Berg, among many others. General Donovan called them his "glorious amateurs."

OSS was a perfect reflection of General Donovan's character: a potent combination of brains, brawn, and bravado. General Donovan encouraged OSS personnel to take risks, frequently telling OSS personnel that, "you can't succeed without taking chances." Leading by example, General Donovan took the same risks himself. Members of OSS volunteered for the most dangerous missions of World War II behind enemy lines to conduct sabotage and guerilla warfare and work with local resistance groups. Their capture by the enemy meant certain death.

Intelligence provided by OSS was critical to the success of Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa. Allen Dulles, chief of OSS operations in Switzerland, secretly negotiated the early surrender of German troops in Northern Italy. Fritz Kolbe, a German diplomat and an OSS asset, provided the U.S. with some of the most valuable intelligence of the war. Some of the most significant contributions came from leading academics in its Research and Analysis division. The Science and Technology branch devised imaginative new weapons and other espionage tools.

Read More...

OSS--Of Swashbuckling Sages

April 2008

The Nation, April 21, 2007

Robert Dreyfuss, in "Hothead McCain" [March 24], describes the Office of Strategic Services, predecessor of the CIA, as a "rambunctious, often out-of-control World War II-era covert-ops team." Led by the legendary "Wild Bill" Donovan, the OSS was a visionary, daring, innovative, unorthodox, effective intelligence organization. It abetted Allied victories in North Africa, Europe, Southeast Asia and elsewhere. Donovan recruited an array of "glorious amateurs," as he called them, including Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Ralph Bunche, Arthur Goldberg, Julia Child, John Ford [and Nation puzzle setter Frank W. Lewis--Ed.]. Many OSS personnel--including my father--risked their lives volunteering for missions behind enemy lines.

Creating a new intelligence service patterned after the OSS is an intriguing notion that deserves serious consideration, not Dreyfuss's casual dismissal.

Charles Pinck, president

The OSS Society

Robert Dreyfuss, in "Hothead McCain" [March 24], describes the Office of Strategic Services, predecessor of the CIA, as a "rambunctious, often out-of-control World War II-era covert-ops team." Led by the legendary "Wild Bill" Donovan, the OSS was a visionary, daring, innovative, unorthodox, effective intelligence organization. It abetted Allied victories in North Africa, Europe, Southeast Asia and elsewhere. Donovan recruited an array of "glorious amateurs," as he called them, including Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Ralph Bunche, Arthur Goldberg, Julia Child, John Ford [and Nation puzzle setter Frank W. Lewis--Ed.]. Many OSS personnel--including my father--risked their lives volunteering for missions behind enemy lines.

Creating a new intelligence service patterned after the OSS is an intriguing notion that deserves serious consideration, not Dreyfuss's casual dismissal.

Charles Pinck, president

The OSS Society

Glorious Amateurs: A New OSS

January 2008

Since 9/11 and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, occasional proposals have been made to re-create the OSS, an ad hoc intelligence organization created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and led by Major General William "Wild Bill" Donovan that holds a special place in the history of intelligence.

Its mission was twofold: first, to provide the President with timely, comprehensive and coordinated intelligence and analysis that he failed to receive from any single government intelligence agency or department, including the military, the State Department, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Secondly, the President wanted to have an independent group that would engage in clandestine and covert actions on many fronts patterned after Britain's Special Operations Executive (SOE), which Winston Churchill directed to "set Europe ablaze."

The OSS had an outstanding record in its secret war. It was so successful that four months after end of the war and six months after Roosevelt's death, the generals and admirals, the State and War Departments, and the FBI conspired to persuade President Truman to disband the organization, which he did, on October 1, 1945.

Consequently, the US did not have an effective intelligence agency during the start of the Cold War. Two years later, Truman realized that he needed the peacetime intelligence agency that Donovan had proposed in 1944 and had, in fact, named the Central Intelligence Agency. On September 18, 1947, Truman signed the National Security Act, creating the CIA. (SOCOM, the US Special Operations Command, also traces its lineage to the OSS.)

Spying is generally an anathema to Americans, especially since some distasteful events have been exposed or revealed during the past sixty years or more. For many reasons, we seemingly have an inbred aversion to clandestine activities. When a secret service's work is not secret, we no longer have a secret service. Or at least a service that has the potentiality of accomplishing much over a period of time. In our time, the CIA is a handy instrument that functions as a centralized punching bag to blame almost every event that appears to go wrong, from geopolitics to warfare. Our national obsession to heap contumely on the CIA emanates from the White House, Congress, the Defense Department, the State Department, the media and the public. The CIA is no longer the prime and first responder to the President. It now reports to the Director of the National Intelligence, an office with some 1,500 staffers. The CIA has a tough time running its own show. How did the OSS succeed? How would we begin to construct a new OSS today?

The creation of the OSS was itself a small miracle made possible only by the strong support of President Roosevelt and his close personal relationship with General Donovan. Their bipartisan relationship should serve as a role model for today's leaders. (After witnessing Donovan fire a silenced .22 caliber pistol designed by the OSS, Roosevelt famously quipped that Donovan was the only Republican he would allow in the Oval Office with a gun. Bipartisanship has its limits.)

The most striking attributes of the OSS were its leadership, the background of its members, and the fact that the organization reported directly to President Roosevelt. In July 1941, before the US entered World War II, Roosevelt accepted Donovan's plan for a new intelligence organization called the Coordinator of Information (COI), which actually was the name of our first peacetime intelligence organization. The COI was a civilian group that reported to the President. After we entered the war, Roosevelt signed a military order on June 13, 1942 establishing the OSS and appointing Donovan as its director. On paper, the OSS was placed under the direction of the Joint Chiefs, but it still had President Roosevelt's ear. A new OSS would need the same independence and presidential support in order to succeed.

Donovan was unconventional, fearless, visionary, imaginative, willing to take the same risks that he asked of others. He took personal responsibility for mistakes. He frequently told OSS personnel that they couldn't succeed without taking chances. He had a facility at selecting and recruiting men and women some of whom reflected his traits. His primary concern was in making OSS an effective force to defeat the enemy. He was renowned for never rejecting any idea of out hand. He built the OSS in his own image, a potent combination of brain, brawn and bravado. In his farewell address, Donovan described the OSS as an "unusual experiment."

OSS veteran Fisher Howe said it best: "If you define leadership as having a vision for an organization and the ability to attract, motivate, and guide others to fulfill that vision, then you have Bill Donovan in spades."

Bureaucracy was anathema to him and most management practices were distended. His hobby was making organizational charts and never following any of them. He often referred to OSS members as "glorious amateurs" and that is precisely what many of them were. He had a talent for hiring people who were beyond the scope of most military leaders. For example, a young woman from Baltimore, who had served in Europe in a minor diplomatic job before Pearl Harbor, wanted to join the OSS and volunteered for risky work, despite losing a leg in a horse riding accident. She became an OSS agent and was sent to occupied France twice to work with the Resistance. Virginia Hall would become the only civilian woman to be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross in World War II.

The OSS was a small, nimble organization with slightly more than 13,000 members. More than sixty percent of its personnel were seconded from the Army, Navy, Marines and Coast Guard. About 4,000 were women and 900 of them served overseas. Contrary to popular perception, OSS personnel came from extremely diverse backgrounds, including Jews, African Americans and recent immigrants from many European countries. To Donovan, they were all his glorious amateurs. Few, if any, had an intelligence background. Consider this mixture: classicists, historians, policemen, artists, lawyers, newspaper editors and writers, archeologists, scientists, college presidents, labor leaders, counterfeiters, bankers, movie actors and directors, economists, baseball players, football players, farmers, and yachtsmen.

What do Saul Steinberg, the artist, John Ford, the movie director, Moe Berg, the baseball player who knew twelve languages, Julia Child, Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, historian and Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Carlton S. Coon, the anthropologist, Norman Holmes Pearson, a professor of English, Stewart Alsop, the columnist, Sterling Hayden, an actor, Paul Mellon, a multi-millionaire, Col. Aaron Bank, the founder of the Green Berets, and Ralph Bunche, a foreign affairs specialist who became the Under Secretary-General of the United Nations and the first African American to win the Nobel Peace Prize, have in common? They were all in the OSS.

It's a safe bet that no organization in American history assembled such a dazzling array of talent. Donovan believed that smart, talented and motivated people could accomplish things. They still can.

Special mention must be made about academics who served in OSS. At least 300 faculty members from leading universities joined the OSS and made significant contributions to the organization's Research and Analysis (R&A) unit. Donovan attributed some of OSS's greatest contributions to this group.

A wise leader of a newly-created OSS might be able to recruit a similar group of remarkable people today and unleash their creativity, much like Donovan did.

Senator McCain and Mitt Romney believe that the revival of the OSS is our best chance to defeat terrorism. But where will they find a visionary leader like General Donovan?

During World War II, Donovan said that his greatest enemies were in Washington, not Europe. Could a new OSS sustain its independence from the large number of formidable bureaucracies that sank the original OSS? Let's hope so.

Its mission was twofold: first, to provide the President with timely, comprehensive and coordinated intelligence and analysis that he failed to receive from any single government intelligence agency or department, including the military, the State Department, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Secondly, the President wanted to have an independent group that would engage in clandestine and covert actions on many fronts patterned after Britain's Special Operations Executive (SOE), which Winston Churchill directed to "set Europe ablaze."

The OSS had an outstanding record in its secret war. It was so successful that four months after end of the war and six months after Roosevelt's death, the generals and admirals, the State and War Departments, and the FBI conspired to persuade President Truman to disband the organization, which he did, on October 1, 1945.

Consequently, the US did not have an effective intelligence agency during the start of the Cold War. Two years later, Truman realized that he needed the peacetime intelligence agency that Donovan had proposed in 1944 and had, in fact, named the Central Intelligence Agency. On September 18, 1947, Truman signed the National Security Act, creating the CIA. (SOCOM, the US Special Operations Command, also traces its lineage to the OSS.)

Spying is generally an anathema to Americans, especially since some distasteful events have been exposed or revealed during the past sixty years or more. For many reasons, we seemingly have an inbred aversion to clandestine activities. When a secret service's work is not secret, we no longer have a secret service. Or at least a service that has the potentiality of accomplishing much over a period of time. In our time, the CIA is a handy instrument that functions as a centralized punching bag to blame almost every event that appears to go wrong, from geopolitics to warfare. Our national obsession to heap contumely on the CIA emanates from the White House, Congress, the Defense Department, the State Department, the media and the public. The CIA is no longer the prime and first responder to the President. It now reports to the Director of the National Intelligence, an office with some 1,500 staffers. The CIA has a tough time running its own show. How did the OSS succeed? How would we begin to construct a new OSS today?

The creation of the OSS was itself a small miracle made possible only by the strong support of President Roosevelt and his close personal relationship with General Donovan. Their bipartisan relationship should serve as a role model for today's leaders. (After witnessing Donovan fire a silenced .22 caliber pistol designed by the OSS, Roosevelt famously quipped that Donovan was the only Republican he would allow in the Oval Office with a gun. Bipartisanship has its limits.)

The most striking attributes of the OSS were its leadership, the background of its members, and the fact that the organization reported directly to President Roosevelt. In July 1941, before the US entered World War II, Roosevelt accepted Donovan's plan for a new intelligence organization called the Coordinator of Information (COI), which actually was the name of our first peacetime intelligence organization. The COI was a civilian group that reported to the President. After we entered the war, Roosevelt signed a military order on June 13, 1942 establishing the OSS and appointing Donovan as its director. On paper, the OSS was placed under the direction of the Joint Chiefs, but it still had President Roosevelt's ear. A new OSS would need the same independence and presidential support in order to succeed.

Donovan was unconventional, fearless, visionary, imaginative, willing to take the same risks that he asked of others. He took personal responsibility for mistakes. He frequently told OSS personnel that they couldn't succeed without taking chances. He had a facility at selecting and recruiting men and women some of whom reflected his traits. His primary concern was in making OSS an effective force to defeat the enemy. He was renowned for never rejecting any idea of out hand. He built the OSS in his own image, a potent combination of brain, brawn and bravado. In his farewell address, Donovan described the OSS as an "unusual experiment."

OSS veteran Fisher Howe said it best: "If you define leadership as having a vision for an organization and the ability to attract, motivate, and guide others to fulfill that vision, then you have Bill Donovan in spades."

Bureaucracy was anathema to him and most management practices were distended. His hobby was making organizational charts and never following any of them. He often referred to OSS members as "glorious amateurs" and that is precisely what many of them were. He had a talent for hiring people who were beyond the scope of most military leaders. For example, a young woman from Baltimore, who had served in Europe in a minor diplomatic job before Pearl Harbor, wanted to join the OSS and volunteered for risky work, despite losing a leg in a horse riding accident. She became an OSS agent and was sent to occupied France twice to work with the Resistance. Virginia Hall would become the only civilian woman to be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross in World War II.

The OSS was a small, nimble organization with slightly more than 13,000 members. More than sixty percent of its personnel were seconded from the Army, Navy, Marines and Coast Guard. About 4,000 were women and 900 of them served overseas. Contrary to popular perception, OSS personnel came from extremely diverse backgrounds, including Jews, African Americans and recent immigrants from many European countries. To Donovan, they were all his glorious amateurs. Few, if any, had an intelligence background. Consider this mixture: classicists, historians, policemen, artists, lawyers, newspaper editors and writers, archeologists, scientists, college presidents, labor leaders, counterfeiters, bankers, movie actors and directors, economists, baseball players, football players, farmers, and yachtsmen.

What do Saul Steinberg, the artist, John Ford, the movie director, Moe Berg, the baseball player who knew twelve languages, Julia Child, Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, historian and Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Carlton S. Coon, the anthropologist, Norman Holmes Pearson, a professor of English, Stewart Alsop, the columnist, Sterling Hayden, an actor, Paul Mellon, a multi-millionaire, Col. Aaron Bank, the founder of the Green Berets, and Ralph Bunche, a foreign affairs specialist who became the Under Secretary-General of the United Nations and the first African American to win the Nobel Peace Prize, have in common? They were all in the OSS.

It's a safe bet that no organization in American history assembled such a dazzling array of talent. Donovan believed that smart, talented and motivated people could accomplish things. They still can.

Special mention must be made about academics who served in OSS. At least 300 faculty members from leading universities joined the OSS and made significant contributions to the organization's Research and Analysis (R&A) unit. Donovan attributed some of OSS's greatest contributions to this group.

A wise leader of a newly-created OSS might be able to recruit a similar group of remarkable people today and unleash their creativity, much like Donovan did.

Senator McCain and Mitt Romney believe that the revival of the OSS is our best chance to defeat terrorism. But where will they find a visionary leader like General Donovan?

During World War II, Donovan said that his greatest enemies were in Washington, not Europe. Could a new OSS sustain its independence from the large number of formidable bureaucracies that sank the original OSS? Let's hope so.

Letter to the Editor

January 2008

In his Dec. 24 column, "Subverting Bush at Langley," Robert D. Novak included a swipe at the Office of Strategic Services, the World War II predecessor of the CIA. Mr. Novak wrote that the OSS "was infiltrated by communists."

The Soviet Union was our ally during World War II. The OSS was not infiltrated by communists during the war; it hired them. They helped to identify native recruits to infiltrate enemy forces and organizations. OSS founder William Donovan reportedly said that he would "put Stalin on the OSS payroll if it would help defeat Hitler."

After the war, a plague of invective assaulted Donovan and the OSS. He was not only accused of harboring communists but of a far worse crime: proposing a peacetime successor to the OSS that critics called a Gestapo. Donovan believed that the main culprit was J. Edgar Hoover, who had vehemently opposed creation of the OSS in 1942. The OSS was disbanded by President Harry S. Truman in 1945.

Regarding Hoover, Donovan once said that his greatest enemies were in Washington, not Europe. Apparently they still are.

Charles Pinck, President

The OSS Society

The Soviet Union was our ally during World War II. The OSS was not infiltrated by communists during the war; it hired them. They helped to identify native recruits to infiltrate enemy forces and organizations. OSS founder William Donovan reportedly said that he would "put Stalin on the OSS payroll if it would help defeat Hitler."

After the war, a plague of invective assaulted Donovan and the OSS. He was not only accused of harboring communists but of a far worse crime: proposing a peacetime successor to the OSS that critics called a Gestapo. Donovan believed that the main culprit was J. Edgar Hoover, who had vehemently opposed creation of the OSS in 1942. The OSS was disbanded by President Harry S. Truman in 1945.

Regarding Hoover, Donovan once said that his greatest enemies were in Washington, not Europe. Apparently they still are.

Charles Pinck, President

The OSS Society

The Best Spies Didn't Wear Suits

December 2004

The New York Times

Before America entered World War II, the intelligence being given to President Franklin D. Roosevelt was incomplete and poorly analyzed by several independent agencies. These included the Office of Naval Intelligence; the Army's intelligence agency, called G2; the Federal Bureau of Investigation; and the intelligence services at the State Department. Much like today's bureaucracies, these agencies did not share information well. But unlike today, there was no centralized intelligence effort focused on foreign threats.

Enter William J. Donovan, known as Wild Bill, who was a World War I Medal of Honor winner, Wall Street lawyer, former United States attorney in Buffalo and 1932 Republican candidate for governor of New York. Although a member of the opposition party, Donovan got along well with Roosevelt, and the men shared an unfashionable belief that America's liberty was threatened by foreign powers.

In the late 30's, Donovan began traveling abroad and informally reporting his findings directly to Roosevelt. Eventually he convinced the president of the need for a centralized spying agency, and in July 1941 Roosevelt created a civilian agency within the White House to oversee American intelligence, naming Donovan to the new post of "coordinator of information."

Eleven months later, and half a year after Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt converted Donovan's group into the O.S.S. under a presidential order. In this the two faced great opposition, particularly from J. Edgar Hoover. (Donovan was later quoted as saying that his "greatest enemies were in Washington, not in Europe.")

Donovan reported directly to the president, even once bringing a silent pistol invented by the O.S.S. into the Oval Office and firing it. Roosevelt responded by telling Donovan he was the only Republican who would be allowed in the Oval Office with a gun.

Perhaps Donovan's greatest skill was his ability to recruit talented men and women from other fields, whether they came from the Ivy League, Wall Street or, believe it or not, prison. (After the war, Gen. William Quinn, then running the Strategic Services Unit, an interim organization created after the dissolution of the O.S.S. in 1945, was alerted by Treasury agents to the presence of master forgers in his ranks. Unknown to Quinn, Donovan had arranged for the release of these men from prison during the war to work for the O.S.S.)

Donovan was willing to try any ideas that he thought had potential and, what was more important, he had the power to act on them. He understood and accepted the inherent risks associated with intelligence work - often telling O.S.S. personnel that "you can't succeed without taking chances" - and was as willing to take responsibility for failures as for successes.

The O.S.S. under Donovan was not an insipid bureaucracy of career-minded professionals. It was a freewheeling organization devoted to finding effective ways of winning a war that imperiled the nation's future, a situation we find ourselves in once again. Donovan found formal decision-making and committees anathema to accomplishing his mission. Rather, he operated on good sense, instincts and experience - and gave the members of his staff great latitude to accomplish their missions as they saw fit.

Another unique feature of the organization was that it encompassed nearly all of the concerns that the C.I.A. and other intelligence organizations are engaged in today. For instance, the special operations branch, which would eventually be the model for the military's Special Forces, was then fully integrated into the other intelligence components. Donovan was also one of the first spy chiefs to recognize the importance of covert action and the need for "actionable intelligence" (information gathered and interpreted quickly enough that action can still be taken to change the situation).

When the war ended, President Harry Truman, who knew little about intelligence issues, disbanded the O.S.S. - only to realize his mistake two years later and create the Central Intelligence Agency. The new agency was different in several important ways, however. The O.S.S. had been an ad hoc group, what Donovan called "an unusual experiment" in unconventional means and methods against the enemy. From its very beginning, however, the C.I.A. was designed not as an experiment but as a permanent government institution. Many of its early leaders, excepting Walter Bedell Smith and Allen Dulles, were distinguished not for their intelligence experience but for their knack for political infighting.

As a peacetime organization, it was often compelled to pursue efficiency rather than effectiveness - it tended to play it safe when picking employees and projects. While this wasn't necessarily a fatal flaw during the cold war, a war of diplomacy and proxy armies in which data collection was often more important than covert action, it would be crippling in the hot war against terrorism.

Thus in the future our agencies should consider the somewhat haphazard way the O.S.S. chose people - unconventional warfare requires unconventional people. In addition, granting tremendous new powers to a "terrorism czar" will work only if that person is, like Donovan, truly independent and above the infighting we will certainly see from the Pentagon and other departments. And last, the new leader must have great leadership ability, intelligence experience and imagination.

Fisher Howe, a leading O.S.S. officer, once said that "if you define leadership as having a vision for an organization, and the ability to attract, motivate and guide followers to fulfill that mission, you have Bill Donovan in spades." In that sense, all the bureaucratic and legislative changes in the world won't matter if we don't find the right person for the job.

Before America entered World War II, the intelligence being given to President Franklin D. Roosevelt was incomplete and poorly analyzed by several independent agencies. These included the Office of Naval Intelligence; the Army's intelligence agency, called G2; the Federal Bureau of Investigation; and the intelligence services at the State Department. Much like today's bureaucracies, these agencies did not share information well. But unlike today, there was no centralized intelligence effort focused on foreign threats.

Enter William J. Donovan, known as Wild Bill, who was a World War I Medal of Honor winner, Wall Street lawyer, former United States attorney in Buffalo and 1932 Republican candidate for governor of New York. Although a member of the opposition party, Donovan got along well with Roosevelt, and the men shared an unfashionable belief that America's liberty was threatened by foreign powers.

In the late 30's, Donovan began traveling abroad and informally reporting his findings directly to Roosevelt. Eventually he convinced the president of the need for a centralized spying agency, and in July 1941 Roosevelt created a civilian agency within the White House to oversee American intelligence, naming Donovan to the new post of "coordinator of information."

Eleven months later, and half a year after Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt converted Donovan's group into the O.S.S. under a presidential order. In this the two faced great opposition, particularly from J. Edgar Hoover. (Donovan was later quoted as saying that his "greatest enemies were in Washington, not in Europe.")

Donovan reported directly to the president, even once bringing a silent pistol invented by the O.S.S. into the Oval Office and firing it. Roosevelt responded by telling Donovan he was the only Republican who would be allowed in the Oval Office with a gun.

Perhaps Donovan's greatest skill was his ability to recruit talented men and women from other fields, whether they came from the Ivy League, Wall Street or, believe it or not, prison. (After the war, Gen. William Quinn, then running the Strategic Services Unit, an interim organization created after the dissolution of the O.S.S. in 1945, was alerted by Treasury agents to the presence of master forgers in his ranks. Unknown to Quinn, Donovan had arranged for the release of these men from prison during the war to work for the O.S.S.)

Donovan was willing to try any ideas that he thought had potential and, what was more important, he had the power to act on them. He understood and accepted the inherent risks associated with intelligence work - often telling O.S.S. personnel that "you can't succeed without taking chances" - and was as willing to take responsibility for failures as for successes.

The O.S.S. under Donovan was not an insipid bureaucracy of career-minded professionals. It was a freewheeling organization devoted to finding effective ways of winning a war that imperiled the nation's future, a situation we find ourselves in once again. Donovan found formal decision-making and committees anathema to accomplishing his mission. Rather, he operated on good sense, instincts and experience - and gave the members of his staff great latitude to accomplish their missions as they saw fit.

Another unique feature of the organization was that it encompassed nearly all of the concerns that the C.I.A. and other intelligence organizations are engaged in today. For instance, the special operations branch, which would eventually be the model for the military's Special Forces, was then fully integrated into the other intelligence components. Donovan was also one of the first spy chiefs to recognize the importance of covert action and the need for "actionable intelligence" (information gathered and interpreted quickly enough that action can still be taken to change the situation).

When the war ended, President Harry Truman, who knew little about intelligence issues, disbanded the O.S.S. - only to realize his mistake two years later and create the Central Intelligence Agency. The new agency was different in several important ways, however. The O.S.S. had been an ad hoc group, what Donovan called "an unusual experiment" in unconventional means and methods against the enemy. From its very beginning, however, the C.I.A. was designed not as an experiment but as a permanent government institution. Many of its early leaders, excepting Walter Bedell Smith and Allen Dulles, were distinguished not for their intelligence experience but for their knack for political infighting.

As a peacetime organization, it was often compelled to pursue efficiency rather than effectiveness - it tended to play it safe when picking employees and projects. While this wasn't necessarily a fatal flaw during the cold war, a war of diplomacy and proxy armies in which data collection was often more important than covert action, it would be crippling in the hot war against terrorism.

Thus in the future our agencies should consider the somewhat haphazard way the O.S.S. chose people - unconventional warfare requires unconventional people. In addition, granting tremendous new powers to a "terrorism czar" will work only if that person is, like Donovan, truly independent and above the infighting we will certainly see from the Pentagon and other departments. And last, the new leader must have great leadership ability, intelligence experience and imagination.

Fisher Howe, a leading O.S.S. officer, once said that "if you define leadership as having a vision for an organization, and the ability to attract, motivate and guide followers to fulfill that mission, you have Bill Donovan in spades." In that sense, all the bureaucratic and legislative changes in the world won't matter if we don't find the right person for the job.