Glorious Amateurs Needed

January 2010 Author:Charles Pinck

Published in Sphere

As Congress prepares to start hearings on the Christmas Day attack on Northwest Airlines Flight 253, there will be an inevitable focus on how to use the latest technology – better databases, full-body scanners and the like – to detect and prevent future attacks.

But the fact is that despite remarkable advances in technology, intelligence remains a distinctly human endeavor. There is no machine that can substitute for a human being's intellect, judgment, instinct or courage.

And if lawmakers want to truly reform our intelligence community, they would be wise to look backward instead of forward – all the way back to World War II's Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor to the CIA and U.S. Special Operations Forces.

This "unusual experiment," as its visionary founder, Maj. Gen. William J. "Wild Bill" Donovan, described it in his 1945 farewell address, succeeded principally because of its diverse and brilliant personnel, many of whom probably would never get admitted into today's intelligence services.

As Congress prepares to start hearings on the Christmas Day attack on Northwest Airlines Flight 253, there will be an inevitable focus on how to use the latest technology – better databases, full-body scanners and the like – to detect and prevent future attacks.

But the fact is that despite remarkable advances in technology, intelligence remains a distinctly human endeavor. There is no machine that can substitute for a human being's intellect, judgment, instinct or courage.

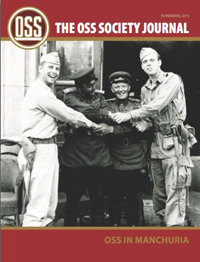

And if lawmakers want to truly reform our intelligence community, they would be wise to look backward instead of forward – all the way back to World War II's Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor to the CIA and U.S. Special Operations Forces.

This "unusual experiment," as its visionary founder, Maj. Gen. William J. "Wild Bill" Donovan, described it in his 1945 farewell address, succeeded principally because of its diverse and brilliant personnel, many of whom probably would never get admitted into today's intelligence services.

They included Virginia Hall (the only civilian woman to receive the Distinguished Service Cross in World War II), Sterling Hayden (who received a Silver Star for his actions behind enemy lines), Moe Berg (who undertook a mission to learn about German efforts to create an atomic bomb) and Ralph Bunche (who would become the first African-American to win the Nobel Peace Prize). Its ranks also included two master forgers released from prison to work for the OSS. Donovan described them as his "glorious amateurs."

William Fairbairn, the legendary expert in hand-to-hand-combat and martial arts, was close to 60 years old when he joined the OSS – and was still able to defeat men less than half his age. Current personnel rules would prevent Fairbairn from applying for a similar position today.

Our intelligence community discourages the type of people who served so valiantly in the OSS from serving today. Let me cite one example to prove this point.

I was contacted several years ago by someone wishing to join our nation's intelligence services. This person's record was nothing less than remarkable. After graduating from high school, he backpacked alone for 18 months across five continents. Along the way he discovered a latent talent for languages and achieved conversational proficiency in three. He went on to get an undergraduate degree in Middle Eastern history from a top university with a 3.9 grade point average. Later, he taught himself Farsi by moving to an Iranian expatriate community, spending thousands of hours learning the language fluently and the culture.

Despite these impressive qualifications, he was unable to elicit any interest from our intelligence community. The only position offered to him was an alternate spot for an intelligence-related summer internship. Had he been alive in World War II, the OSS would have grabbed him in a second.

Donovan said he would "rather have a young lieutenant with enough guts to disobey a direct order than a colonel too regimented to think and act for himself" and constantly reminded OSS personnel that they "could not succeed without taking chances."

The OSS was designed to do great things. William Casey said of the OSS that "you didn't wait six months for a feasibility study to prove that an idea could work. You gambled that it might work. You didn't tie up the organization with red tape designed mostly to cover somebody's ass. You took the initiative and the responsibility. You went around end; you went over somebody's head if you had to. But you acted. That's what drove the regular military and the State Department chair-warmers crazy about the OSS."

These are the same qualities our intelligence services so badly need today to win our war with terrorists.

___________________

Charles T. Pinck is president of The OSS Society and is a partner in The Georgetown Group, an investigative and security services firm.

William Fairbairn, the legendary expert in hand-to-hand-combat and martial arts, was close to 60 years old when he joined the OSS – and was still able to defeat men less than half his age. Current personnel rules would prevent Fairbairn from applying for a similar position today.

Our intelligence community discourages the type of people who served so valiantly in the OSS from serving today. Let me cite one example to prove this point.

I was contacted several years ago by someone wishing to join our nation's intelligence services. This person's record was nothing less than remarkable. After graduating from high school, he backpacked alone for 18 months across five continents. Along the way he discovered a latent talent for languages and achieved conversational proficiency in three. He went on to get an undergraduate degree in Middle Eastern history from a top university with a 3.9 grade point average. Later, he taught himself Farsi by moving to an Iranian expatriate community, spending thousands of hours learning the language fluently and the culture.

Despite these impressive qualifications, he was unable to elicit any interest from our intelligence community. The only position offered to him was an alternate spot for an intelligence-related summer internship. Had he been alive in World War II, the OSS would have grabbed him in a second.

Donovan said he would "rather have a young lieutenant with enough guts to disobey a direct order than a colonel too regimented to think and act for himself" and constantly reminded OSS personnel that they "could not succeed without taking chances."

The OSS was designed to do great things. William Casey said of the OSS that "you didn't wait six months for a feasibility study to prove that an idea could work. You gambled that it might work. You didn't tie up the organization with red tape designed mostly to cover somebody's ass. You took the initiative and the responsibility. You went around end; you went over somebody's head if you had to. But you acted. That's what drove the regular military and the State Department chair-warmers crazy about the OSS."

These are the same qualities our intelligence services so badly need today to win our war with terrorists.

___________________

Charles T. Pinck is president of The OSS Society and is a partner in The Georgetown Group, an investigative and security services firm.