Historical Footnote On Press Leaks

December 2007 Author:Dan Pinck

The following bulleted references reveal the ingredients of the evidence:

A grand jury was convened in Chicago in the late spring of 1942 to consider violations of the Espionage Act by the Chicago Tribune. A brief summation of the newspaper’s actions is based on the following: in late May of 1942 our Navy cryptographers decoded a Japanese navy cipher, JN-25-C, used by Admiral Yamamoto who stated that he intended to invade Midway. Admiral Nimitz decided to gamble on the Navy intercepts: he sent three aircraft carriers and other warships northeast of Midway to intercept the Japanese force. On June 4, 1942, our planes sank all four of Japan’s aircraft carriers with all of their planes. This was our first victory in World War II, and it severely decimated Japan’s forces in the Pacific.

Three days later, on June 7, 1942, a page one article titled Navy Had Word Of Jap Plan To Strike At Sea appeared in the Chicago Tribune and in its two sister newspapers, the New York News and the Washington Times-Herald. Joseph Medill Patterson, the publisher and founder of the New York Daily News, and his sister, Eleanor “Cissy” Medill Patterson, publisher of the Washington Times-Herald, were both cousins of McCormick. The article was syndicated by the Tribune to its sister newspapers in which it was titled Naval Chiefs Knew Strength of Enemy. The first paragraph was: “Washington, June 7. – The strength of the Japanese forces with which the American Navy is battling somewhere west of Midway Island in what is believed to be the war’s greatest naval battle, was well-known in American naval circles, reliable sources in the naval intelligence disclosed here tonight.” N. B. The dateline from Washington also appeared in the Tribune. The reason for it was to hide or suppress the real source of the information and to attribute its origin to “reliable sources in naval intelligence.” Basing the origin in Washington was as sneaky as you could get.

The source of this information was an Australian-born, Tribune war correspondent, Stanley Johnston, embedded on the cruiser New Orleans, on its way to Pearl Harbor. He stole the JN-25-C decryption from the captain’s cabin. It contained the Japanese order of battle at Midway. He wrote his report and filed it from Honolulu, without submitting it to a censor. His managing editor, J. Loy Maloney, arranged for the dateline and simultaneous publication in New York and Washington to cover the Chicago Tribune from wrongdoing.

Almost anyone with an alert mind reading this article would deduce that a Japanese code had been broken. The instant reaction created the desire in the White House and the military to try McCormick and his newspaper – and his sister newspapers – for treason. If the Japanese knew that their codes had been compromised, they would obviously change them. On August 7, 1942, Francis Biddle, our Solicitor General, announced that a Grand Jury would be convened in Chicago to investigate Johnston’s article. The Jury met and heard the testimony of the editors of the three newspapers and the reporter, Stanley Johnston, during five days. On the sixth day, the Jury was dismissed, because Navy officers did not show up to testify. Navy officials decided it would be foolhardy to risk further publicity about the broken Japanese code. A bill of indictment meant a public trial, with public testimony in a court of law. The Statute of Limitations expired by the end of the war. Grant Sanger, M. D. wrote in U. S. Naval Institute Proceedings (September 1977): “I agree with the late Judge Thomas D. Thacher, Solicitor General 1930-1933, that if the Navy had seen fit to present evidence to the Chicago Grand Jury in 1942 on the background of how we got Admiral Yamamoto’s plan of operation, those responsible for the article would have been indicted for treason.”

There’s no reason to believe that all U. S. Congressmen kept the secret knowledge secret. One of them didn’t. On the floor of the House, Rep. Elmer J. Holland, of Pennsylvania, lambasting the Tribune, said: “American boys will die because of this article,” adding “somehow our Navy had secured and broken the secret code of the Japanese Navy.” His speech went out on the wire services.

So far as we know, the Japanese never learned that we had broken their code; at least, they never made any great changes to it. Or, if they were informed, they didn’t believe it. It was a Harry Potter miracle that Japanese agents or sympathizers didn’t send this information to Japan.

Don’t assume for a second that this was the only Tribune disclosure of a military secret that was a possible violation of the Espionage Act of 1917. It wasn’t. Another revelation might have harmed the United States in its European war to a deleterious extent. On December 4, 1941 – three days before Pearl Harbor – the Tribune ran a story under this headline: “FDR’s War Plans! Goal is Ten Million Armed Men, Proposed Land Drive By July, 1943.” In the story itself, this sentence appeared: “If our European enemies are to be defeated, it will be necessary for the United States to enter the war.” And: “July 1, 1943 was the date set for America’s presumed entry.” The Army War Plans Division produced what they called the Rainbow Five plan; in it were potential German targets, maps of Germany, and military equipment needed to fight the war in Europe. It was a contingency plan but it contained enough information to give Hitler an opportunity to shape his own strategic plans. Who leaked this to the Chicago Tribune? Senator Burton K. Wheeler of Montana gave the Five Year plan to Chesly Manly, the newspaper’s Washington correspondent. (In the interest of full disclosure, I note that I attended Sidwell Friends School in Washington and met some of the major players in the government, including Wheeler, and that I rarely ever looked at the Times-Herald but, nontheless, knew that it was, as James Thurber might say, further right than a soup spoon. One of its favorite columnists, Westbrook Pegler, was the only war correspondent, and the youngest, kicked out of Europe by General Pershing in World War I. Francis Biddle, the attorney general, believed that McCormick could be prosecuted under the Espionage Act of 1917. No action was taken.

But this isn’t all. The Tribune went for a trifecta of perfidy near the end of the war. This is what happened. Walter Trohan, the newspaper’s Washington correspondent whose string of vile reporting equaled his longevity (he died at age one hundred), wrote an article that appeared simultaneously in the Tribune and the Times-Herald on February 9, 1945. This time, the newspapers aimed to cover their tails by printing the following at the beginning of the report: “The Washington Times-Herald and the Chicago Tribune yesterday secured exclusively a copy of a highly confidential memorandum from Brig.

General William J. Donovan, director of the Office of Strategic Services, which coordinates intelligences information, to President Roosevelt proposing to set up the super-spy agency....Only 15 copies of the memorandum and draft order were made, each plastered with secrecy injunctions.” Never mind that General Donovan was a Major General, Trohan often got large and small things wrong. The Office of Strategic Services was the forerunner of the CIA and it had an honorable record during the war, with upwards of four hundred men and women behind enemy lines in Europe and Asia. Turning on his thought-button, Trohan observed that “neither Mr. Roosevelt nor General Donovan expect the end of the war to usher in an era of perpetual peace.” On August 22, 1945, Trohan shifted into high gear in an article headlined “OSS Survival Plan Attacked As Plot for U. S. Super-Gestapo/ Congress Prepares to Unearth Secrets of Donovan’s Mix of Bankers and Reds.” Trohan reported that OSS stood for “Only Select Slackers” and “Oh, Strickly Soviet.” He lined up a host of Republican Congressmen for quotes, calling the proposed organization a Gestapo or an OGPU. Striving again for a safety net, the Tribune stated at the end of Trohan’s article: “Although these documents and those submitted to the White House by General Donovanwere made available to the Chicago Tribune, they were never officially in possession of this newspaper. They were copied by its representative on paper belonging to the Tribune.” Ouch. A CIA historian tried to identify the source of the leak; he said that the most likely culprit was Harry Hopkins, Roosevelt’s closest aide.

Two of the Tribune’s World War II correspondents based in Germany were so taken with Germany that they remained there during the war. One of them, Donald Day, worked for German radio the last year of the war. He lambasted President Roosevelt and the Allied war against Germany. Apparently, he was a cross between Ezra Pound, who derided everything American in broadcasts from Italy, and Lord Haw-Haw (William Joyce), a British turncoat who broadcast, in Engish, from Germany. Day’s dispatches were printed in the Tribune and in its family-related newspapers.

Beyond a doubt, McCormick was a weird and despicable character. A. J. Liebling, one of our best press critics, in a Wayward Press column in The New Yorker (March 25, 1950) reported that McCormick said, in an interview with a Tribune correspondent in Cairo: “France is atheist and anarchic. Her greatest patriot, Petain, is held in prison by his political opposition.” In Bombay, McCormick denounced “President Truman’s civil-rights program as a new form of slavery” and, in Bermuda, on his way home, he reported: “All the police are white. On the other hand, the colored people are contented and extremely well off.” George Seldes, another noted critic of the press, wrote that in Chicago, “a free press meant that the Tribune was free to print without constraint such as truth.” (sic)

We need new words and insights to define what’s happening now. Ideally, I’d like to have a joint series of columns by Liebling and George Orwell. I’ll rest for the present an observation that Liebling made in 1961: “I think that anybody who talks often with people about newspapers nowadays must be impressed by the growing distrust of the information they contain.” Then and now, nothing changes.

A grand jury was convened in Chicago in the late spring of 1942 to consider violations of the Espionage Act by the Chicago Tribune. A brief summation of the newspaper’s actions is based on the following: in late May of 1942 our Navy cryptographers decoded a Japanese navy cipher, JN-25-C, used by Admiral Yamamoto who stated that he intended to invade Midway. Admiral Nimitz decided to gamble on the Navy intercepts: he sent three aircraft carriers and other warships northeast of Midway to intercept the Japanese force. On June 4, 1942, our planes sank all four of Japan’s aircraft carriers with all of their planes. This was our first victory in World War II, and it severely decimated Japan’s forces in the Pacific.

Three days later, on June 7, 1942, a page one article titled Navy Had Word Of Jap Plan To Strike At Sea appeared in the Chicago Tribune and in its two sister newspapers, the New York News and the Washington Times-Herald. Joseph Medill Patterson, the publisher and founder of the New York Daily News, and his sister, Eleanor “Cissy” Medill Patterson, publisher of the Washington Times-Herald, were both cousins of McCormick. The article was syndicated by the Tribune to its sister newspapers in which it was titled Naval Chiefs Knew Strength of Enemy. The first paragraph was: “Washington, June 7. – The strength of the Japanese forces with which the American Navy is battling somewhere west of Midway Island in what is believed to be the war’s greatest naval battle, was well-known in American naval circles, reliable sources in the naval intelligence disclosed here tonight.” N. B. The dateline from Washington also appeared in the Tribune. The reason for it was to hide or suppress the real source of the information and to attribute its origin to “reliable sources in naval intelligence.” Basing the origin in Washington was as sneaky as you could get.

The source of this information was an Australian-born, Tribune war correspondent, Stanley Johnston, embedded on the cruiser New Orleans, on its way to Pearl Harbor. He stole the JN-25-C decryption from the captain’s cabin. It contained the Japanese order of battle at Midway. He wrote his report and filed it from Honolulu, without submitting it to a censor. His managing editor, J. Loy Maloney, arranged for the dateline and simultaneous publication in New York and Washington to cover the Chicago Tribune from wrongdoing.

Almost anyone with an alert mind reading this article would deduce that a Japanese code had been broken. The instant reaction created the desire in the White House and the military to try McCormick and his newspaper – and his sister newspapers – for treason. If the Japanese knew that their codes had been compromised, they would obviously change them. On August 7, 1942, Francis Biddle, our Solicitor General, announced that a Grand Jury would be convened in Chicago to investigate Johnston’s article. The Jury met and heard the testimony of the editors of the three newspapers and the reporter, Stanley Johnston, during five days. On the sixth day, the Jury was dismissed, because Navy officers did not show up to testify. Navy officials decided it would be foolhardy to risk further publicity about the broken Japanese code. A bill of indictment meant a public trial, with public testimony in a court of law. The Statute of Limitations expired by the end of the war. Grant Sanger, M. D. wrote in U. S. Naval Institute Proceedings (September 1977): “I agree with the late Judge Thomas D. Thacher, Solicitor General 1930-1933, that if the Navy had seen fit to present evidence to the Chicago Grand Jury in 1942 on the background of how we got Admiral Yamamoto’s plan of operation, those responsible for the article would have been indicted for treason.”

There’s no reason to believe that all U. S. Congressmen kept the secret knowledge secret. One of them didn’t. On the floor of the House, Rep. Elmer J. Holland, of Pennsylvania, lambasting the Tribune, said: “American boys will die because of this article,” adding “somehow our Navy had secured and broken the secret code of the Japanese Navy.” His speech went out on the wire services.

So far as we know, the Japanese never learned that we had broken their code; at least, they never made any great changes to it. Or, if they were informed, they didn’t believe it. It was a Harry Potter miracle that Japanese agents or sympathizers didn’t send this information to Japan.

Don’t assume for a second that this was the only Tribune disclosure of a military secret that was a possible violation of the Espionage Act of 1917. It wasn’t. Another revelation might have harmed the United States in its European war to a deleterious extent. On December 4, 1941 – three days before Pearl Harbor – the Tribune ran a story under this headline: “FDR’s War Plans! Goal is Ten Million Armed Men, Proposed Land Drive By July, 1943.” In the story itself, this sentence appeared: “If our European enemies are to be defeated, it will be necessary for the United States to enter the war.” And: “July 1, 1943 was the date set for America’s presumed entry.” The Army War Plans Division produced what they called the Rainbow Five plan; in it were potential German targets, maps of Germany, and military equipment needed to fight the war in Europe. It was a contingency plan but it contained enough information to give Hitler an opportunity to shape his own strategic plans. Who leaked this to the Chicago Tribune? Senator Burton K. Wheeler of Montana gave the Five Year plan to Chesly Manly, the newspaper’s Washington correspondent. (In the interest of full disclosure, I note that I attended Sidwell Friends School in Washington and met some of the major players in the government, including Wheeler, and that I rarely ever looked at the Times-Herald but, nontheless, knew that it was, as James Thurber might say, further right than a soup spoon. One of its favorite columnists, Westbrook Pegler, was the only war correspondent, and the youngest, kicked out of Europe by General Pershing in World War I. Francis Biddle, the attorney general, believed that McCormick could be prosecuted under the Espionage Act of 1917. No action was taken.

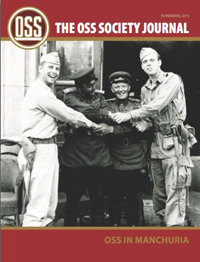

But this isn’t all. The Tribune went for a trifecta of perfidy near the end of the war. This is what happened. Walter Trohan, the newspaper’s Washington correspondent whose string of vile reporting equaled his longevity (he died at age one hundred), wrote an article that appeared simultaneously in the Tribune and the Times-Herald on February 9, 1945. This time, the newspapers aimed to cover their tails by printing the following at the beginning of the report: “The Washington Times-Herald and the Chicago Tribune yesterday secured exclusively a copy of a highly confidential memorandum from Brig.

General William J. Donovan, director of the Office of Strategic Services, which coordinates intelligences information, to President Roosevelt proposing to set up the super-spy agency....Only 15 copies of the memorandum and draft order were made, each plastered with secrecy injunctions.” Never mind that General Donovan was a Major General, Trohan often got large and small things wrong. The Office of Strategic Services was the forerunner of the CIA and it had an honorable record during the war, with upwards of four hundred men and women behind enemy lines in Europe and Asia. Turning on his thought-button, Trohan observed that “neither Mr. Roosevelt nor General Donovan expect the end of the war to usher in an era of perpetual peace.” On August 22, 1945, Trohan shifted into high gear in an article headlined “OSS Survival Plan Attacked As Plot for U. S. Super-Gestapo/ Congress Prepares to Unearth Secrets of Donovan’s Mix of Bankers and Reds.” Trohan reported that OSS stood for “Only Select Slackers” and “Oh, Strickly Soviet.” He lined up a host of Republican Congressmen for quotes, calling the proposed organization a Gestapo or an OGPU. Striving again for a safety net, the Tribune stated at the end of Trohan’s article: “Although these documents and those submitted to the White House by General Donovanwere made available to the Chicago Tribune, they were never officially in possession of this newspaper. They were copied by its representative on paper belonging to the Tribune.” Ouch. A CIA historian tried to identify the source of the leak; he said that the most likely culprit was Harry Hopkins, Roosevelt’s closest aide.

Two of the Tribune’s World War II correspondents based in Germany were so taken with Germany that they remained there during the war. One of them, Donald Day, worked for German radio the last year of the war. He lambasted President Roosevelt and the Allied war against Germany. Apparently, he was a cross between Ezra Pound, who derided everything American in broadcasts from Italy, and Lord Haw-Haw (William Joyce), a British turncoat who broadcast, in Engish, from Germany. Day’s dispatches were printed in the Tribune and in its family-related newspapers.

Beyond a doubt, McCormick was a weird and despicable character. A. J. Liebling, one of our best press critics, in a Wayward Press column in The New Yorker (March 25, 1950) reported that McCormick said, in an interview with a Tribune correspondent in Cairo: “France is atheist and anarchic. Her greatest patriot, Petain, is held in prison by his political opposition.” In Bombay, McCormick denounced “President Truman’s civil-rights program as a new form of slavery” and, in Bermuda, on his way home, he reported: “All the police are white. On the other hand, the colored people are contented and extremely well off.” George Seldes, another noted critic of the press, wrote that in Chicago, “a free press meant that the Tribune was free to print without constraint such as truth.” (sic)

We need new words and insights to define what’s happening now. Ideally, I’d like to have a joint series of columns by Liebling and George Orwell. I’ll rest for the present an observation that Liebling made in 1961: “I think that anybody who talks often with people about newspapers nowadays must be impressed by the growing distrust of the information they contain.” Then and now, nothing changes.