William Donovan and Special Operations

August 2008 Author:Bob Bergin

by Bob Bergin

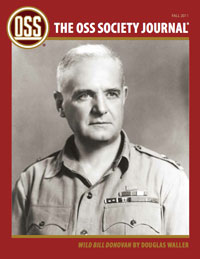

Special operations conducted by the OSS during World War II were the foundation on which the U.S. Special Forces were built, and the basis for the special operations conducted by U.S. forces today. The Special Operations (SO) Branch was one of two major divisions created by William Donovan when he organized the OSS. Donovan’s thinking on the role and the nature of special operations is as relevant today as it was in the early days of World War II.

A July 30, 2008 Washington Post article “Strategy against Al-Qaeda Faulted” cites a major new Rand Corporation study critical of the course the U.S. is following in what has become known as the “war on terrorism”. The study advocates that terrorists should be described as criminals, not warriors, and argues that the fight against terrorists is better waged by law enforcement agencies than armies. According to the Post, the authors of the study say that “when military forces are needed, the emphasis should be on local troops, which understand the terrain and culture and tend to have greater legitimacy. In Muslim countries in particular, there should be a ‘light military footprint or none at all.’”

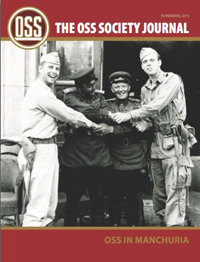

Donovan’s thinking was most recently expressed by Major General John K. Singlaub in an interview published in the November issue of WWII History. Singlaub was a young OSS officer when he parachuted into German-occupied France in 1944 to organize, train and lead a French Resistance unit. Later he was sent to China to train Vietnamese guerrillas to operate in Japanese-occupied Indochina.

Singlaub commented on William Donovan’s thinking about special operations even before the U.S. became directly involved in World War II: “President Roosevelt had authorized William “Wild Bill” Donovan, who later conceived and organized the OSS, to go to Great Britain in 1940 to look into things like espionage that we didn’t know very much about. Donovan came back and tried to introduce the American leadership to what he called ‘the fourth dimension of warfare’. The first and second dimensions were land and naval warfare; the third, air warfare, was introduced in World War I. The Fourth dimension, Donovan said, was to organize the enemy’s rear areas to our advantage. The idea was to help people under German occupation and use them to achieve our objectives. It’s what my group was heading for.”

Later in the same interview, when asked what most struck him as he looked back over a long and eventful career, Singlaub said: “It’s clear that Donovan really understood that Special Operations were to be conducted as unconventional warfare. We were given a mission and sent off to it with resources we had, whether we were in occupied France, China, or Vietnam. We went in with very small teams. The concept was that we would train the indigenous people and let them conduct the operations. Today we’re losing that. The emphasis now seems to be on direct action – to launch an attack with our own highly trained people to kill the enemy or kick down doors. There seems to be too much emphasis on the direct action part of special operations – rather than keeping our own participation low, and training the indigenous people to do the job.”

Special operations conducted by the OSS during World War II were the foundation on which the U.S. Special Forces were built, and the basis for the special operations conducted by U.S. forces today. The Special Operations (SO) Branch was one of two major divisions created by William Donovan when he organized the OSS. Donovan’s thinking on the role and the nature of special operations is as relevant today as it was in the early days of World War II.

A July 30, 2008 Washington Post article “Strategy against Al-Qaeda Faulted” cites a major new Rand Corporation study critical of the course the U.S. is following in what has become known as the “war on terrorism”. The study advocates that terrorists should be described as criminals, not warriors, and argues that the fight against terrorists is better waged by law enforcement agencies than armies. According to the Post, the authors of the study say that “when military forces are needed, the emphasis should be on local troops, which understand the terrain and culture and tend to have greater legitimacy. In Muslim countries in particular, there should be a ‘light military footprint or none at all.’”

Donovan’s thinking was most recently expressed by Major General John K. Singlaub in an interview published in the November issue of WWII History. Singlaub was a young OSS officer when he parachuted into German-occupied France in 1944 to organize, train and lead a French Resistance unit. Later he was sent to China to train Vietnamese guerrillas to operate in Japanese-occupied Indochina.

Singlaub commented on William Donovan’s thinking about special operations even before the U.S. became directly involved in World War II: “President Roosevelt had authorized William “Wild Bill” Donovan, who later conceived and organized the OSS, to go to Great Britain in 1940 to look into things like espionage that we didn’t know very much about. Donovan came back and tried to introduce the American leadership to what he called ‘the fourth dimension of warfare’. The first and second dimensions were land and naval warfare; the third, air warfare, was introduced in World War I. The Fourth dimension, Donovan said, was to organize the enemy’s rear areas to our advantage. The idea was to help people under German occupation and use them to achieve our objectives. It’s what my group was heading for.”

Later in the same interview, when asked what most struck him as he looked back over a long and eventful career, Singlaub said: “It’s clear that Donovan really understood that Special Operations were to be conducted as unconventional warfare. We were given a mission and sent off to it with resources we had, whether we were in occupied France, China, or Vietnam. We went in with very small teams. The concept was that we would train the indigenous people and let them conduct the operations. Today we’re losing that. The emphasis now seems to be on direct action – to launch an attack with our own highly trained people to kill the enemy or kick down doors. There seems to be too much emphasis on the direct action part of special operations – rather than keeping our own participation low, and training the indigenous people to do the job.”